News

By Natasha Riveron, October 15, 2019

This October, we kicked off our new webinar series, Complete Streets 301: Putting people first, with our first webinar, “Building Complete Streets: The developer’s perspective.” A recording of the webinar is now available. You can also download a PDF of the presentation or read the brief recap below.

A discussion recap

Calvin Gladney, President and CEO of Smart Growth America kicked off the webinar by sharing his experience as a former real estate developer. He outlined the larger connection between land use and Complete Streets: the way we use land largely dictates how we are able or unable to access community amenities like schools, grocery stores, offices, and places of worship. Because private developers largely create those places, it’s important to establish collaboration from the very beginning of the planning process between the nonprofit, public, and private sectors to ensure that community, equity, and sustainability are a priority.

Michael Lander, a Minneapolis-based real estate developer and member of the LOCUS steering committee, shared his vision of what Complete Streets actually look like in practice. He then highlighted what he sees as the top issues preventing localities from building Complete Streets.

Michael emphasized that there is a strong economic argument for Complete Streets because they are demonstrated to increase property values. He also cited Foot Traffic Ahead, a report that outlines the economic argument that walkable places enhances real estate value with the data to back it up.

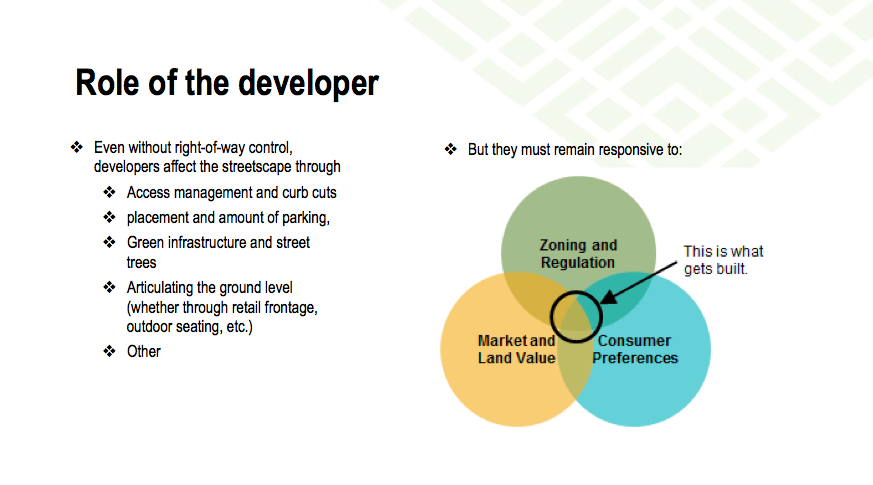

Next, we welcomed Andrew Peng from Jair Lynch, a DC-Based real estate investment and development company. Andrew explained the unique role of the developer to improve the streetscape, even if they don’t necessarily own the right of way. Andrew finished up his portion by sharing strong examples of private/public collaboration to work toward incorporating Complete Streets.

Questions?

We had so many great questions during the Q&A section of the webinar that we couldn’t get to all of them. We followed up with Michael and Andrew to discuss answers to some of the questions we missed.

Q: Are you noticing any developers that are Public Benefit Corporations, less focused just on return on investment financially?

ML: Some developers are taking a ‘triple bottom line’ view. While there is market support for the real estate value of a great public realm, most capital providers are focused on the money in the short term.

AP: Essentially no even non-profit developers have to think about project returns, just their financing sources may look different.

Q: For art in public right of way, is there usually a maintenance memorandum of understanding (MOU)?

ML: Yes. Someone has to agree to maintain it. That can be a private property owner, arts district council, etc.

Q: Have you worked on projects that required integrated low-income housing as a percentage of total housing units or anything similar, such as maybe rent control to go along with the project (if needed based on the location)?

ML: Yes, that is very common these days. Regardless of the project, developers should try to have top quality architectural design and public realm— no more building slums.

AP: Yes; you are describing inclusionary zoning, which is applied in many municipalities (DC included) and requires a minimum percentage of units maintained at a certain affordability level for all new projects. Things like planned unit developments (PUDs) will also often have inclusionary ordinances as part of the agreement, as was the case with McMillan. As for rent control, that’s rarely applied at a project level; there’s usually a citywide policy on that and which properties it affects.

Q: I’ve lived in a city that is going through major changes in street usage (Seattle) and moved 15 years ago to a smaller, transitioning city that doesn’t have the supportive infrastructure like well-developed public transportation. The growing pains that this smaller community is experiencing is challenging as it becomes a bedroom community to Portland (Oregon) and is working to balance the older, smaller-town residents who are nostalgic for “the way it’s always been or used to be” and the need to address and attract a new, younger population that wants more contemporary planning philosophies like Complete Streets. So, is there any process or community exercise that we could consider in beginning an “everyone together” dynamic to help change expectations and show how to plan together?

ML: Good question. That’s a big challenge. The best strategy is getting ‘same talking to same’. If older residents like it ‘the way it is,’ other senior residents could talk about the benefits of walkable, mixed-use, mixed-age environments. They can discuss how ADU’s and other ‘new planning’ ideas actually allow and support extended family/multi-generational living. Make sure to talk and educate people in the context of what benefits them and avoid ‘planning speak.

Q: How are the future needs of the streets, like self-driven vehicles, considered in the design of the infrastructure?

ML: This is a very important area. It’s critical we don’t just trade in single occupancy with a driver for single occupancy without one. New technology will allow the 12 person van—not possible with human drivers. Additionally, all that parking needs to be repurposed for other uses, not just more vehicle capacity. Parking lanes becoming driving lanes would seriously degrade the pedestrian environment.

Q: Have the speakers seen any success with changing policy for roadway section and parking requirements relative to changing technologies (driverless cars which will allow more throughput than standard-driven cars) and ride-sharing (which would reduce parking demand)?

ML: I have seen this mostly in parking requirements and allocation of right of way—more space for bikes. Progressive cities (like San Francisco, Portland, and others) are eliminating parking requirements, adding bike lanes, and aggressively moving away from ‘auto only’ street designs, often against pushback from drivers who are used to being ‘king of the road.’

Related News

© 2025 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing