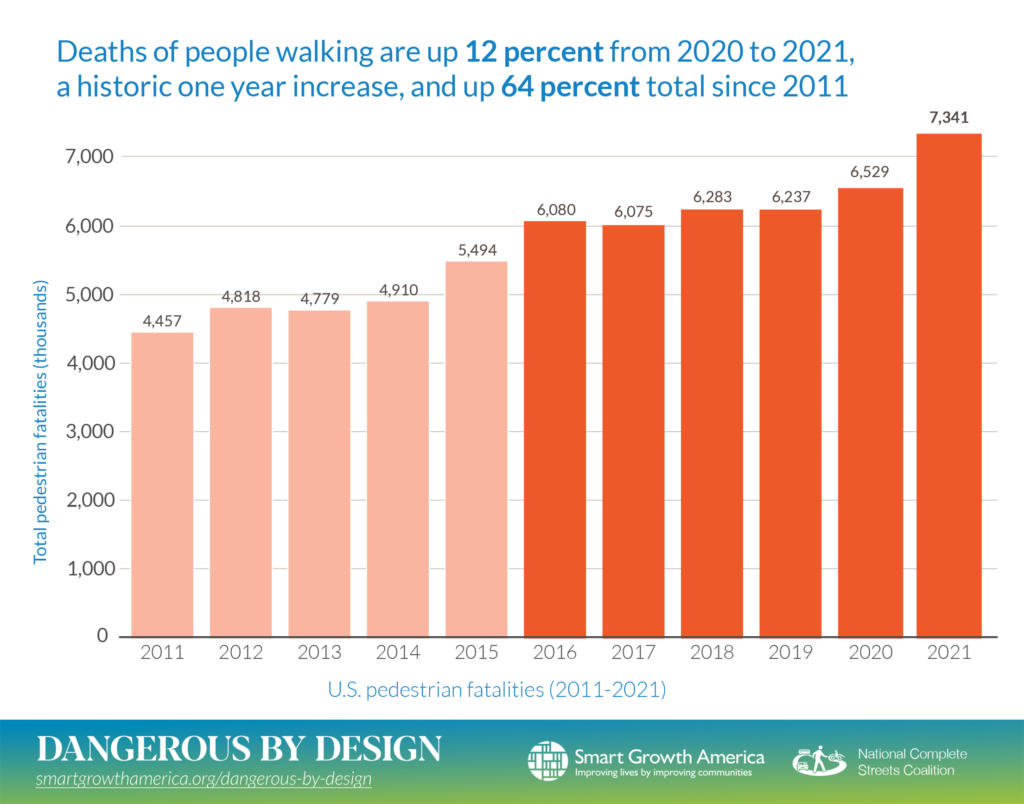

Traffic fatalities continue to plague communities across the U.S. with an estimated 42,795 people killed in 2022. This trauma is not experienced equally—people walking, people of color, and people in low-income communities are far more likely to be killed. But the most significant danger—especially for people walking, biking, rolling, or otherwise not in a vehicle—is located on a disproportionately smaller percentage of all roads: two-thirds of all deaths in urbanized areas occur on state-owned arterial roads. Improving the safety of communities, increasing physical activity, and eliminating preventable deaths can be achieved by better collaboration between local communities and state agencies.

Smart Growth America (SGA), with support from CDC’s Active People, Healthy Nation initiative℠, launched the Complete Streets Leadership Academies in Alaska, California, Connecticut, and Tennessee to equip and train local agencies and state departments of transportation to collaborate, innovate, and commit to making changes together to address safety on these dangerous state-owned roads. Cohorts were selected to plan and implement “quick-build” demonstration projects, a way to pilot and test new ideas and street designs to activate streets and better support walking, biking, and rolling.

About the Complete Streets Leadership Academies

The Complete Streets Leadership Academies (CSLA), launched in November 2022, combined a series of virtual sessions and in-person workshops to develop and pilot processes to effectively deploy community-led quick-build projects on state-owned roads. Program participants included city or county staff, engineers, planners, public health practitioners, and community advocates. The sessions and workshops covered the basics of quick-build projects including site selection, design, community engagement, and data collection. SGA challenged participants to deploy a quick-build project during the program and consider how to apply the lessons learned from the demonstration to inform future safety interventions and the processes that would support further innovation. Participating communities received grants between $10,000 and $15,000 to support the implementation of their projects.

The Complete Streets Leadership Academies (CSLA), launched in November 2022, combined a series of virtual sessions and in-person workshops to develop and pilot processes to effectively deploy community-led quick-build projects on state-owned roads. Program participants included city or county staff, engineers, planners, public health practitioners, and community advocates. The sessions and workshops covered the basics of quick-build projects including site selection, design, community engagement, and data collection. SGA challenged participants to deploy a quick-build project during the program and consider how to apply the lessons learned from the demonstration to inform future safety interventions and the processes that would support further innovation. Participating communities received grants between $10,000 and $15,000 to support the implementation of their projects.

Smart Growth America designed these Academies with three key factors in mind.

- New Strategies: With the majority of all traffic fatalities occurring on state-owned arterial roads, current approaches to street design are not working—new strategies are needed to significantly move the needle on safety and health, by making walking, biking, and rolling easier, safer, and more convenient on these roads.

- Quick-build demonstration projects: Years of SGA experience have repeatedly demonstrated the powerful impact of quick-build demonstration projects to test specific designs and interventions. But in these four states and most other states SGA has worked in, no process exists within the state DOT for deploying quick-build demonstration projects. These processes are desperately needed to make this proven strategy more feasible.

- Improved collaboration: SGA wanted to foster improved collaboration between state DOTs, local jurisdictions, and other key partners including public health professionals around a common goal of creating safer communities.

It is worth noting that SGA required state DOTs to be the lead applicant for participation in this program. Without the partnership, dedication, and leadership of the state DOT, any local policy or intervention will likely run up against significant challenges on a state-owned road due to the inability to make design changes without seeking approval first from the state DOT. This is often a lengthy process that can result in a community being forced to change its vision due to state guidelines or plans. This early demonstration of commitment was critical to this program’s success and led state DOTs to consider how to better incorporate quick-builds across their entire states going forward.

Overall, the program aimed to create a space and a project where state DOTs, local jurisdictions, and community and public health partners could come together to:

Lessons from this program’s quick-build projects

After working across these four states, SGA collected numerous important insights for working on quick-builds collaboratively with state DOTs, local jurisdictions, and community and health partners. In fact, the dangers for people walking and biking may never be fully addressed without applying these program lessons on some level. The projects profiled on the following pages—and the lessons gleaned from them—can provide a road map for other states and local jurisdictions to implement demonstration projects and improve both safety and health.

After working across these four states, SGA collected numerous important insights for working on quick-builds collaboratively with state DOTs, local jurisdictions, and community and health partners. In fact, the dangers for people walking and biking may never be fully addressed without applying these program lessons on some level. The projects profiled on the following pages—and the lessons gleaned from them—can provide a road map for other states and local jurisdictions to implement demonstration projects and improve both safety and health.

Improved communication and increased opportunities for collaboration between state DOTs and local jurisdictions helped facilitate the development of these pedestrian safety interventions.

Many participants noted that the program helped them connect with people who can be important allies at the state or local level. The peer-to-peer learning structure made each project stronger with feedback from neighboring communities. The participants notably felt the release of tension and shared excitement over the program as the group transitioned from weekly Zoom calls to the in-person workshop. A shared project created space for state DOTs and local jurisdictions to come together to navigate barriers, pool resources, and strive for shared success.

These projects would have proved difficult to impossible without state DOTs creating the space, time, and resources to identify and implement new approaches.

The quick-build projects were a major undertaking for each state DOT and local jurisdiction. These projects were an additional task for often already overburdened teams in terms of staff time, resources, and funding. However, each participant’s commitment to show up supported exploring a relatively under-utilized approach to improving safety, health, and accessibility. There can be too little time and space for staff to test new ideas, explore emerging best practices, and build cross-sectoral partnerships.

The most successful projects resulted from strong leadership and clear intent from state DOT decision makers to redefine what a successful street looks like.

Program participants received various levels of engagement and buy-in from state DOTs. When state DOT leadership was engaged in the program, DOT staff could operate with confidence and in good faith when obstacles inevitably cropped up, working with teams to find workable solutions. Without this commitment from the top, many of these projects could have stalled out at multiple points along the way. Participants demonstrated leadership by sharing candidly, participating actively, and continuing to show up in the face of challenges. Continued support from state DOT leadership will be a factor in whether these states can continue to experience the successes resulting from quick-build projects.

The four stages of collaboration

While every state and city team was unique and evolved to reflect their specific context and participants, we saw some clear phases each state would go through as they progressed through the program. Those who were successful continued to move through these stages. Understanding these phases that naturally occur and what is needed to move through them may help other states or jurisdictions looking to improve coordination around traffic safety.

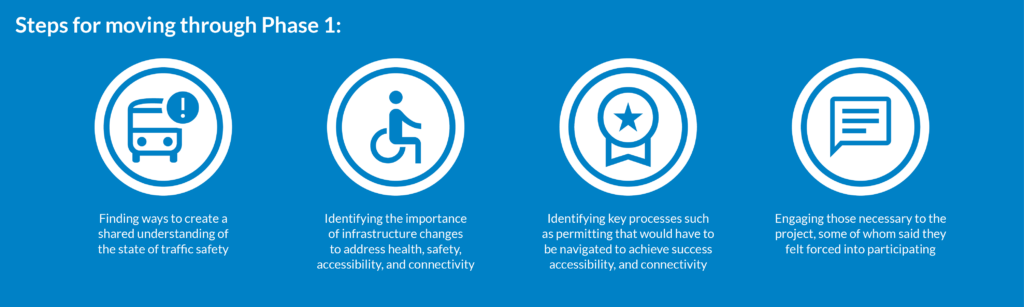

1. Taking (realistic) stock of the situation

Participants were generally enthusiastic about participating in the Complete Streets Leadership Academy. However, some of that optimism waned as it quickly became clear that expectations were not the same on all sides. Participants ranged along a spectrum, from thinking the process would be simple to navigate, all the way to feeling doomed from the very first meeting. Some even felt that the problem areas proposed to be addressed (safety, accessibility, etc.) were already being addressed through other initiatives and found it challenging to establish a clear goal and see the value of this project. But those who were able to be clear-eyed about the challenges and the current state of things were best poised to find ways to overcome them.

2. Acknowledging past challenges in collaboration

Many of the state and local representatives had interacted previously in their roles with varying levels of success. Frustration came out from both sides as they recounted previous attempts to implement changes.

3. If at first you don’t succeed…

Few of the projects that were ultimately implemented were the initial proposed ideas—nearly every single project evolved during the collaborative process. State DOTs and local jurisdictions in our program were in constant negotiation over things such as permits, materials, and scope. Moving forward required in some cases expanding the project design to do more than originally intended, or even starting over from scratch.

4. We all win together

The majority of proposed projects were installed Successful implementation was a result of joint ownership, a willingness to work together to continue forward in the face of challenges, and a shared commitment to the fact that the status quo needs to be changed. The participants who understood that the negotiations, ever-changing obstacles, and capacity challenges were part of the journey and not a complete derailment were ultimately the ones that were the most successful. Even the teams that were ultimately unable to field a quick-build project benefited from challenging existing ideas about how to confront traffic safety. While a completed project was the ultimate goal, everyone involved can benefit from constantly learning new strategies and tactics, building partnerships, and remaining open to creating a system where all community members can move around safely.

Reporting on Alaska, California, Connecticut, and Tennessee

In November 2022, we launched Leadership Academies in Alaska, California, Connecticut, and Tennessee. Through our case studies, we walk you through each participating community’s project and what was learned along the way. These case studies were written by Smart Growth America staff, derived from SGA’s direct participation in the program, participant surveys, and interviews and discussions with project leaders. Project leads at the state and local levels provided feedback on the drafts and approved the language in the case studies.

Alaska

The state of Alaska, the largest and northernmost state of the U.S., has unique circumstances that present challenges to safe street design. Heavy winter snow and ice wear down traffic paint, and dark winter months and long summer days require different lighting solutions for people walking, cycling, and driving. But even with all of its differences, Alaska has many things in common with other U.S. states, including the fact that the majority of traffic fatalities occur on state-owned roadways. Ultimately, Alaska’s participation in the Complete Streets Leadership Academy didn’t result in the implementation of a quick-build project. However, DOT&PF did succeed in building a stronger relationship with a local community dedicated to advancing safer streets, and their staff learned a great deal in the process.

Read the case study:

California

California has worked to strengthen its commitment to Complete Streets in recent years including the adoption of a Director’s Policy on Complete Streets and a Complete Streets Action Plan, as well as the development of decision-making procedures and dedicated funding targets. However, Caltrans and cities across the state continue to disagree and face challenges when it comes to making changes to unsafe, high-speed state-owned roads that cut through communities. Through their participation in the Academy, they wanted to strengthen their partnership with local agencies and learn lessons that can inform future statewide guidance to better enable other similar projects in the future.

Read the case studies:

Berkeley, CA San Leandro, CA South San Francisco, CA

Connecticut

Despite being one of the smallest states in the country, Connecticut has not been immune to the nationwide increase in traffic fatalities. The Connecticut cohort brought together leadership, staff, and community members to take advantage of an opportunity to work alongside one another to make changes on the state-owned roads. By the end of the program, the state recognized the value of quick-build demonstrations in achieving their traffic safety goals and had taken steps to utilize them as a tool elsewhere.

Read the case studies:

Bristol, CT Middletown, CT Waterbury, CT

Tennessee

In light of a recent increase in alarming traffic fatalities, Tennessee has made strides to improve its focus on multimodal users and safety in the last few years, including its recent Statewide Active Transportation Plan and the creation of the Multimodal Access Policy requiring every Tennessee DOT (TDOT) project to consider multimodal infrastructure. The Complete Streets Leadership Academy training and resulting projects will inform the creation of a process and policy to more easily enable local- and state-administered quick-build demonstration projects.

Read the case studies:

There is power in doing something concrete, even if temporary.

The National Complete Streets Coalition (NCSC) at Smart Growth America has long made it clear that we need safer, more productive roadways to allow people to enjoy more active transportation and the health benefits it brings. To help communities experiment with this approach, NCSC has been developing and iterating a “leadership academy” model over the last five years bringing together cohorts of local leaders to build capacity, foster collaboration, and test out tangible street design changes through quick-build demonstration projects.

The quick-build projects we’ve facilitated have been overwhelmingly successful at making streets safer for people walking, biking, and rolling—backed up by the data collected and the experiences of the communities we have worked with. We’ve learned that combining a desire for change with an opportunity to collaborate on an innovative, temporary project produces improved relationships, an increased willingness to embrace Complete Streets, and meaningful, permanent street design changes that improve safety and access to physical activity.

The quick-build projects we’ve facilitated have been overwhelmingly successful at making streets safer for people walking, biking, and rolling—backed up by the data collected and the experiences of the communities we have worked with. We’ve learned that combining a desire for change with an opportunity to collaborate on an innovative, temporary project produces improved relationships, an increased willingness to embrace Complete Streets, and meaningful, permanent street design changes that improve safety and access to physical activity.

But this locally-focused approach has always had a major limitation: the most deadly and dangerous roads for people walking, biking, or rolling are often owned by the state DOT. They are usually designed to be highways, even if that road doubles as Main Street. These roads can also be the hardest to make safer for people outside of vehicles because they were built or designed to move high-speed traffic through the area, even if they need to provide access to local jobs, stores, schools, and the other local destinations people need on a daily basis.

While trying something new is not always easy to execute on city-owned streets—especially in places that have little experience with Complete Streets—the degree of difficulty goes up significantly when dealing with state-owned roads. This is what we wanted to confront head-on with this new series we launched in late 2022. What we learned alongside this cohort of leaders from four states and ten cities reinforced much of what we’ve learned over our years of work with dozens of other communities elsewhere.

Demonstration projects at their core acknowledge that the status quo approach to designing, deploying, and measuring success on our streets is failing to keep people safe and make healthier options like walking more convenient. But based on our experience, even those practitioners who recognize the need for change and are eager to test out new approaches may lack any sort of established practice for demonstration projects, requiring them to start from scratch to create new processes and policies to enable quick-build demonstration projects. They also are required to develop this on their own with little guidance or direction from the transportation field.

We’ve heard through our years of work, including most recently with participants in this program, that state DOT staff often feel left on their own to determine whether a non-traditional safety treatment they may like to try out is permitted by USDOT and the Manual of Uniform Traffic ControlDevices (MUTCD)—even if it has a proven track record of improving safety. There is a great opportunity for federal leaders to work with states, local leaders, and safety and public health partners to foster and support more learning through demonstration projects with proactive new guidance and spaces for state DOT staff to share their own experiences and propagate lessons to others.

There is power in doing something concrete, even if temporary. Physical changes to street design demonstrate that safety, health, and accessibility are important priorities, and that solving the crisis of traffic fatalities and severe injuries needs both creativity and immediate action. These academies provided an opportunity for champions to come together and harness their innovation and creativity, share their experiences and frustration, and make tangible safety and public health improvements. That’s exactly what we need more of to make safer roadway designs the default.

Beth Osborne

Vice President of Transportation and Thriving Communities, Smart Growth America

Acknowledgments

Smart Growth America would like to thank the many participants of the Complete Streets Leadership Academies in Alaska, California, Connecticut, and Tennessee. Justice + Joy, Stantec, ThinkTN, and Toole Design provided technical expertise and support throughout the program and in drafting this report and 3M generously provided support for quick-build project installation and materials.

This program and report was developed with funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity (Cooperative Agreement CDC-RFA-OT18-1802). The views presented in this product do not necessarily reflect the views and/or positions of CDC.

These efforts are part of the CDC’s Active People, Healthy Nation℠ Initiative that is working to help 27 million Americans become more physically active by 2027. Active People, Healthy Nation supports strategies that increase physical activity through community design including Complete Streets. Learn more: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/activepeoplehealthynation/index.html.