News

By Kennedy O'Dell, October 1, 2025

Today is the first day of a government shutdown of uncertain length and consequence–read on for a reminder of what a government shutdown usually looks like, and what we’re watching for in the current environment of rescissions, partisan fracturing, and reductions in force.

At 12:01 this morning, the federal government shut down after Congress failed to pass a seven-week government funding extension led by Congressional Republicans. The measure passed the Republican-controlled House but failed in the Senate, where it required 60 votes—and the support of Democrats—to pass. While two Democrats and one independent voted with Republicans in favor of the funding bill, Senate Democrats largely stuck together and voted down the bill, refusing to provide the votes to pass the measure after doing so last fiscal year, only to then see the Trump Administration pursue an aggressive campaign of legally dubious rescissions, staff cuts, and politically-motivated slow walking of program implementation. “Nobody has any incentive to reach a deal if it’s not going to be honored,” Politico reported Senator Merkley of Oregon saying, as he expressed his concerns around the Trump Administration’s implementation of a funding deal. While Democrats have tied their negotiating position on the funding package to healthcare provisions, the tension around the separation of powers and fundamental ability of Congress to determine spending for the country is an underlying issue roiling the debate and driving some of the dynamics of the shutdown.

In the midst of this turbulence, it’s helpful to revisit how the federal funding process traditionally works and what a government shutdown has looked like in the past. With that background in mind, we then ask what’s next, given the unusual present situation–a difficult question, but one with a set number of possible paths.

How is the federal government funding process supposed to work?

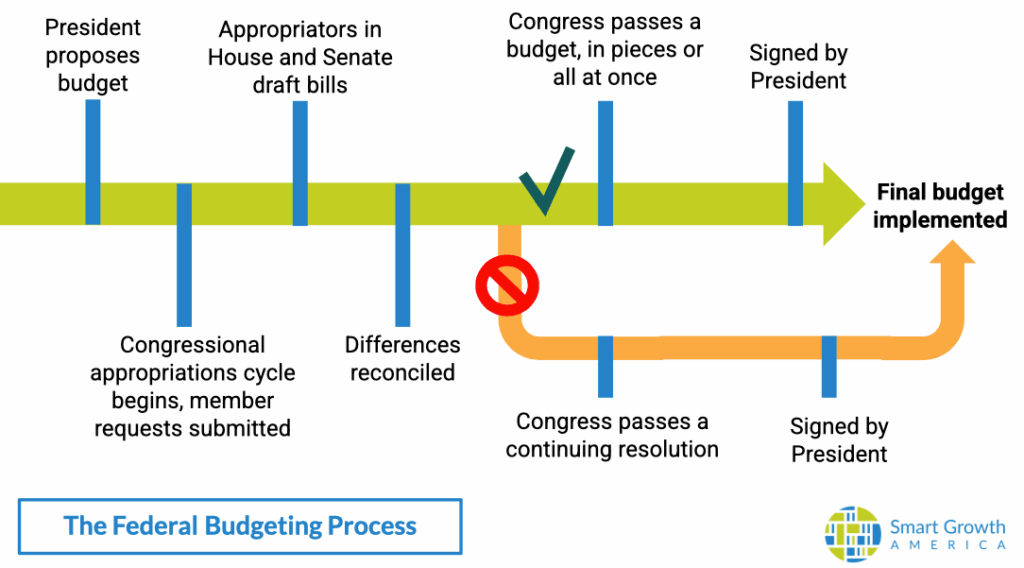

Under the Constitution, the responsibility to appropriate funds for government operations falls to the Legislative Branch. Congress executes this responsibility through the House and Senate Appropriations Committees and the yearly appropriations process. Each year, the President proposes a budget, and then the House and Senate Appropriations committees create draft legislation based on the President’s request, as well as requests from their constituents and other members of Congress. The House and Senate each draft 12 appropriations bills via 12 subcommittees that focus on specific related topics within the federal government, such as Homeland Security, Agriculture, and Energy and Water Development. After these drafts are completed and their differences are reconciled, Congress begins trying to pass a consolidated version of each of the 12 bills. The bills can either be passed individually or bundled together in comprehensive packages known as omnibuses. If Congress passes a handful of appropriations bills but fails to pass others, it can trigger a partial government shutdown.

If Congress cannot agree on the funding levels for a new suite of funding bills, an alternative path is a continuing resolution (indicated in the chart above with the orange arrow). A continuing resolution is an agreement to reference last year’s funding amounts across programs–essentially an agreement that a new deal can’t be struck, but that funding must be provided so last year’s levels will do for now. Continuing resolutions (CRs) are typically viewed as a cut to funding because they don’t allow for standard inflationary adjustments to programs, usually prohibit agencies from initiating new programs or activities, and can vary in length. Short-term CRs can be used to buy more time to negotiate a full-year funding deal, while year-long CRs are a last-ditch effort alternative to a full-year funding deal. Lastly, anomalies–meaning exceptions to the duration, amount, or purposes that funds can be used for that don’t align with what’s laid out in the rest of the CR—and legislative language can be included in CRs.

What is a government shutdown?

A government shutdown occurs if Congress does not pass a government funding bill of some kind–either a full suite of appropriations bills or a continuing resolution–by September 30th in a given year. Broadly speaking, a government shutdown requires federal agencies to pause their activity, furlough workers, and spin down their activity to what is minimally required for safety or essential work functions of the government. In practice, what this means varies from agency to agency and from presidential administration to presidential administration because a great deal of discretion around the design and implementation of a shutdown plan falls to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). For example, the Trump Administration, under the leadership of OMB Director Russ Vought, has threatened to go beyond the standard practice of furloughing federal workers during a shutdown and instead seek further reductions in force. For now, the HUD Contingency Plan for the lapse in appropriations is available here, the EPA Contingency Plan is available here, and the DOT Contingency Plan is available here. The contingency plans provide preliminary guidance on staffing and operations plans during the shutdown at the respective agencies.

What happens next?

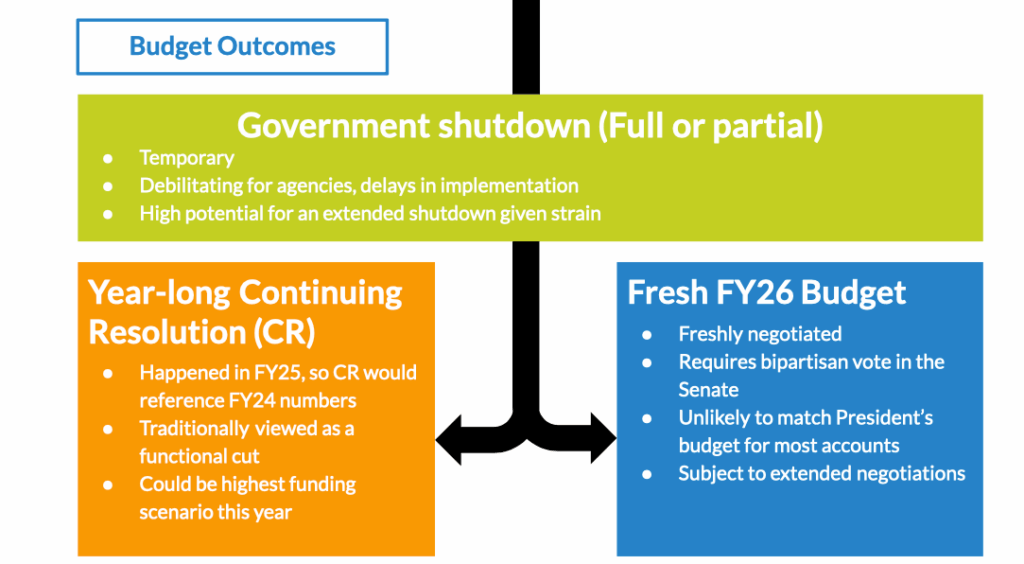

There are three likely paths forward in the coming weeks, with some hybrid of the three a fourth option: a sustained shutdown, a year-long continuing resolution, and the successful negotiation of a new FY26 budget. The shutdown seems likely to drag on for at least a few weeks, and a half-new-half-old funding situation could occur if Congress were to be able to successfully negotiate a new budget for a select group of agencies and accounts but fail to reach an agreement and have to go on a year-long continuing resolution for the remaining agencies (unlikely but not impossible). What actually happens will be dictated by the political will of each side in the negotiations–Democrats have made it clear they’d like to see some forward movement on healthcare negotiations as a requirement for their cooperation on funding, although the posture varies between members of Congress on what degree of movement might be enough to garner the votes needed to pass a government funding bill. There’s also some question of who voters blame for any pain they experience as a result of the shutdown and subsequent threatened cuts to federal government staffing. Democrats already lost three members of their caucus on last night’s government funding vote–Senators Fetterman, Cortez Masto, and King–and Republicans only need a handful more Democrats to join them to pass a bill.

The shutdown length remains uncertain–the immediate path forward is unclear, as is the extent to which the American public will blame either or all parties involved for the fallout from the shutdown. As the shutdown continues, Smart Growth America plans to monitor and provide updates on the impact of staff cuts and work freezes on transportation, housing, and land use work in communities across the country. Receive important updates by subscribing to our newsletter.

Related News

© 2026 Smart Growth America. All rights reserved

Site By3Lane Marketing